May 2014

Daniël de Blocq van Scheltinga +852 2530 0611

daniel.dbvs@polarwide.com

Paul Hodges +44 (0)20 7700 6100

phodges@iec.eu.com

China Accelerates its Reform of the Financial Sector

Executive Summary

- Reform of the Financial Sector in China is

a key stepping stone towards implementing the major reforms outlined in the Third Plenum

- Developments in Alibaba’s online money

market fund “Yu’E Bao” and in shadow

banking have acted as catalysts to speed up the pace of reform

- The aim is to make access to capital easier

for healthy companies, and more expensive for problem firms, irrespective of

whether they are state-owned or private

- This “level playing field” with regard to

access to capital will make it easier for companies to invest and grow in China

1. Introduction

Chart 1:

China’s Official and Shadow Bank Lending, 2009 – 2014 Q1

China’s lending programme since 2009 has

been the largest in the world at over $10tn.

As Chart 1 shows, its official lending totalled $7tn at the end of

March, with estimates of so-called ‘shadow lending’ suggesting this was now around

$3.5tn, half the size of official lending.

By comparison, total US Federal Reserve lending though its Quantitative

Easing programme currently amounts to $3.9tn.

The financial sector reforms announced at

China’s Third Plenum last November thus have implications well beyond China

itself, as we discussed in our March note (Will

Market forces Start to Play a Role in China?). The government’s aim is to start to allow

“market forces to play a decisive role”, in line also earlier commitments made

when China joined the World Trade Organisation.

Before discussing the implications of this

development, it is important to first understand how China’s financial sector

currently operates. The key point is

that the Chinese banking sector is an integral part of the state:

- In China the state-owned banks are the financial system, with nearly all financial risk concentrated on their balance sheets - whether through official or shadow bank lending

- The heart of the system includes just four banks (commonly referred to as the "Big Four") namely the Bank of China; China Construction Bank; Industrial and Commercial Bank of China; and Agricultural Bank of China

- These and the other major banks are all owned by the government, either through the Chinese Investment Corporation (CIC) or through the Ministry of Finance

- This ownership is focused through a holding company, Central SAFE Investments (known as "Huijin"), which CIC acquired in 2007. Other "minority" shareholders in Huijin are mainly State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs), and are therefore also part of the government

- A further sign of state involvement came in 2012, when China's central bank (the People's Bank of China) tool a $50bn holding in CIC

Day-to-day

operations are similarly controlled by the government as it chooses the Huajin board

members. Thus as a foreign banker

working in one of the major banks explained to us, currently “all of the board

members of different banks are trained in the same way, think in the same way,

view risk in the same way, and structure their organisations in the same way”.

The

implications of this can be seen in the handling of the 2009 stimulus packages,

when the banks were the conduit for the government. They lent the stimulus money to business,

with the majority of the cash going directly to the SOE sector. Essentially, therefore, it is fair to say

that the major banks are currently used by the government to implement or fine-tune

economic policy.

2.

The impact of

Yu’E Bao and shadow banking on reform

This close

linkage between government and banks means that the decision to reform the

financial system has major implications for the entire SOE sector, and is a key

part of the move to reform it. Importantly, though, the need to speed up the

reform process has been made imperative by the rapid growth of Yu’E Bao,

established in June 2013 by Ali Baba, China’s giant internet marketplace:

- Yu’E Bao (literally meaning: leftover treasure), is a new product offered by Alipay, the online payment service of Ali Baba

- It allows Alipay account holders to invest idle cash balances in money market funds online

- These funds pay higher interest rates than the banks, with deposits redeemable on demand

- Its growth over the past 10 months has been truly remarkable: it is now China’s largest money market fund with 81 million investors, and deposits of Rmb 40bn ($87bn)

- This growth clearly caught the authorities by surprise, with a Huijin vice-chairman admitting to the South China Morning Post that “the emergence of Alibaba’s Yu‘E Bao online money market fund has prompted the authorities to speed up reform in the financial sector”.

In addition,

there is the issue of the shadow banking system, which has come into global

prominence in the past 2 years, whilst

the authorities have been trying to stabilise official lending. Shadow banking was originally established in

the early 1980s, as an informal mechanism by which privately-owned companies could

lend to each other to fund their development.

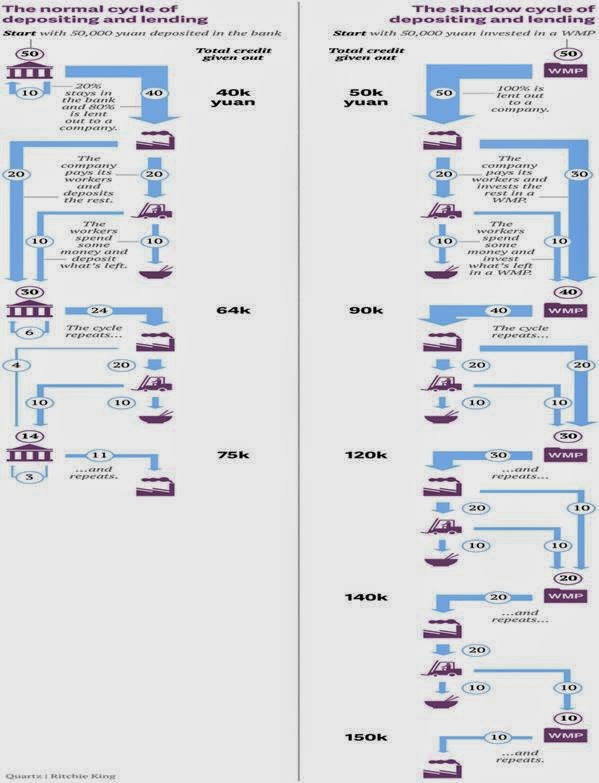

(The Appendix provides a chart explaining the different lending

mechanisms operated by the official and shadow banking systems.)

But today it has

grown to become a core part of China’s financial system with its capital provided

by private and public sector organisations.

These include trust companies (often owned by the banks), as well as corporates

and local government financial vehicles.

Individuals are also lenders, with

many ordinary Chinese attracted by the promise of potentially high

returns.

As the Appendix shows, it does not retain reserves against bad debts and

other costs. Thus its recent rapid

growth has prompted major concern due to (a) it being very lightly regulated

(b) its role in helping to circumvent official lending limits and (c) its lending

being associated with weak credit standards and potentially unenforceable

repayment guarantees.

3.

First steps on

the reform path

3.

First steps on

the reform path

Yu’E Bao’s

success, allied to the need to better regulate the shadow banking sector, has thus

underlined the need for major Chinese banks to be able to provide similar

products to their customers. This can

clearly only occur as a result of reform.

Two examples highlight the changes now underway:

- CITIC Securities recently obtained approval to establish China’s first real estate investment trust, although this will still be a private offering and not publicly listed and traded

- Even more importantly, the government has allowed real estate developer Zhejiang Xingrun to go bankrupt owing Rmb 3.5bn ($563m). This was clearly meant as a wake-up call to investors, to encourage them to take responsibility for assessing the credit-worthiness of the bonds in which they invested, and not to assume government would always provide support

A further step

also seems likely, following a comment by the governor of China’s central bank

that “deposit-rate liberalisation is on our agenda," especially as he went

on to add that “I personally think it’s very likely to be realised in a year or

two."

This would be a

very important milestone, as it would create proper competition between banks

and businesses such as Yu'E Bao. It

would also further reinforce the message that market forces should be playing

“the decisive role”. Lenders will not

only have to analyse risks properly, but will also need to allocate more funds

to credit-worthy private firms, who are able to pay higher rates than SOEs.

It is also a

very aggressive timeframe, underlining the growing urgency of the new

leadership with regard to implementing its reform agenda, and overcoming

powerful vested interests.

These measures are important first steps in levelling

the playing field between the SOEs and private companies. They will mean that access to capital will

become more market-driven, and make it easier for wholly-owned foreign

enterprises to obtain onshore funding. At the same time, the move towards more

risk-based pricing for loans will help to promote necessary reform and

consolidation in the SOE sector, by identifying the weaker players.

APPENDIX

China’s official and shadow banking systems in action

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

About Polarwide: Polarwide is a Hong Kong-based financial and strategic advisory firm advising international companies with their Asian strategy.

Daniël de Blocq van Scheltinga

was the first foreigner to be granted permission to run the finance company of a top-tier Chinese State Owned Enterprise, when establishing and managing ChemChina Finance Company. Previously, Daniël held a variety of senior positions in corporate and investment banking, including as Asia Pacific Head of Chemicals and Asia Head Asset Based Finance for ABN AMRO.

He has lived in Hong Kong for 14 years, and continues to spend much of his time in China, advising both international and Chinese firms, as well as leaders in the public and private sectors. Daniël is a graduate of Leiden University in the Netherlands, holding a Master of Law degree with a speciality of International law.

About IeC: IeC is a London-based strategy consultancy advising Fortune 500 and FTSE 100 companies, investment banks and fund managers.

Paul Hodges

is a trusted adviser to major companies and the investment community, and has a proven track record of accurately identifying key trends in global marketplaces. He has been widely recognised for correctly forewarning of the 2008 global financial crisis. His analysis of the key role of demographics in driving the global economy is now attracting increasing interest from senior policymakers and executives.

Paul is Chairman of International eChem (IeC) and non-executive Chairman of NiTech Solutions Ltd. Prior to launching IeC in 1995, Paul spent 17 years with Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI), both in England and the USA, where he held senior executive positions in petrochemicals and chloralkali, and was Executive Director of a $1 billion ICI business. Paul is a Freeman of the City of London and is a graduate of the University of York, and subsequently studied with the IMD business school in Switzerland

Disclaimer

This Research Note has been prepared by Polarwide/IeC for general circulation. The information contained in this Research Note may be retained. It has not been prepared for the benefit of any particular company or client and may not be relied upon by any company or client or other third party. Polarwide/IeC do not give investment advice and are not regulated under the UK Financial Services Act. If, notwithstanding the foregoing, this Research Note is relied upon by any person, IeC/Polarwide do not accept, and disclaim, all liability for loss and damage suffered as a result.

© IeC/Polarwide 2014